Газета «Новости медицины и фармации» Гастроэнтерология (553) 2015 (тематический номер)

Вернуться к номеру

ACG Clinical Guideline: Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Авторы: Keith D. Lindor, MD, FACG (1, 2), Kris V. Kowdley, MD, FACG (3), M. Edwyn Harrison, MD (2)

(1) — College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona, USA

(2) — Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, Arizona, USA

(3) — Liver Care Network and Organ Care Research, Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, Washington, USA

Рубрики: Гастроэнтерология

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

Статья опубликована на с. 38-42

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic cholestatic liver disease that can shorten life and may require liver transplantation. The cause is unknown, although it is commonly associated with colitis. There is no approved or proven therapy, although ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is used by many on an empiric basis. Complications inclu–ding portal hypertension, fat-soluble vitamin deficiency, metabolic bone diseases, and development of cancers of the bile duct or colon can occur.

Epidemiology

Gender. Approximately 60–70 % of patients with PSC and ulcerative colitis (UC) are men, and age at diagnosis is usually 30–40 years [1]. Among patients without UC, there is a slight female predominance.

Diagnosis

Recommendations

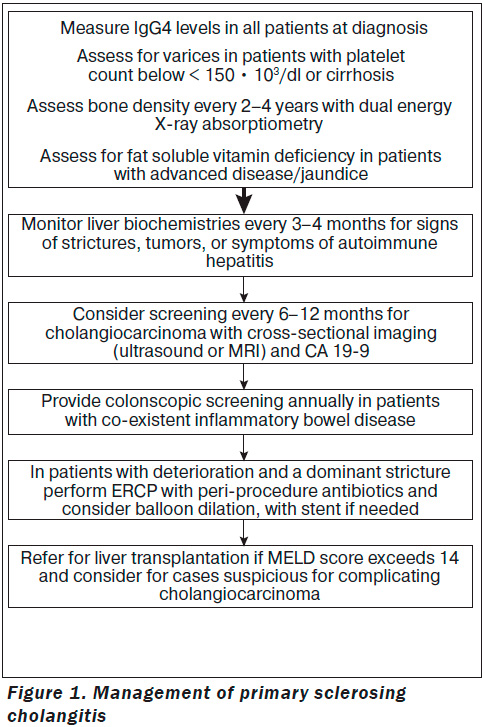

1. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreato–graphy (MRCP) is preferred over endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to establish a diagnosis of PSC (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [4, 5, 20].

2. Liver biopsy is not necessary to make a diagnosis in patients with suspected PSC based on diagnostic cholangiographic findings (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence) [21].

3. Liver biopsy is recommended to make a diagnosis in patients with suspected small duct PSC or to exclude other conditions such as suspected overlap with autoimmune hepatitis (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [22–24].

4. Antimitochondrial autoantibody testing can help exclude primary biliary cirrhosis (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [25].

5. Patients with PSC should be tested at least once for elevated serum immunogloblulin G4 (IgG4) levels (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [26–28].

Signs and Symptoms

A large number of patients present without symptoms and come to attention simply by a finding of persistently abnormal liver tests. When symptoms occur, fatigue maybe the most commonly noted finding but it is nonspecific. Sudden onset of pruritus should signal the possibility of obstruction of the biliary tree. Other symptoms are those of advanced liver disease such as jaundice or gastrointestinal bleeding. Many patients with PSC may have inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD); hence, bleeding from the colon should lead to consideration of IBD as well as bleeding from portal hypertension. Abdominal distention with fluid and confusion are late symptoms, as is jaundice. Some patients may have fever and pain arising from cholangitis and other patients experience chronic right upper quadrant discomfort; however, right upper quadrant pain is not a promi–nent feature of PSC.

Biochemical Tests

Blood tests usually show a cholestatic profile with predominate elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level. Gamma-glutamyl transferase will be elevated if obtained and the aminotransferases are often times only modestly elevated. Bilirubin and albumin levels are oft en normal at the time of diagnosis, although these levels may become increasingly abnormal as the disease progresses. Hypergammaglobulinemia is not a common finding, although IgM levels are found to be increased in ~ 50 % of patients [31]. In recent years, elevations of serum levels of IgG4 have been found in ~ 10 % of patients with PSC and may represent a distinct subset [26–28]. The patients who have elevated IgG4 levels tend to have a more rapidly progressive disease in the absence of treatment. Unlike patients with typical PSC, patients with IgG4-associated disease and PSC do appear to respond to corticosteroids [26, 32]. All patients with PSC should be tested at least once for elevated serum IgG4 levels [26–28].

Medical Treatment

Recommendation

1. UDCA in doses > 28 mg/kg/day should not be used for the management of patients with PSC (strong recommendation and high quality of evidence) [42].

Differential diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis:

— secondary sclerosing cholangitis;

— cholangiocarcinoma;

— IgG4-associated cholangitis;

— histiocytosis X;

— autoimmune hepatitis;

— HIV syndrome;

— bile duct strictures;

— choledocholithiasis;

— primary biliary cirrhosis;

— papillary tumors.

— secondary sclerosing cholangitis;

— cholangiocarcinoma;

— IgG4-associated cholangitis;

— histiocytosis X;

— autoimmune hepatitis;

— HIV syndrome;

— bile duct strictures;

— choledocholithiasis;

— primary biliary cirrhosis;

— papillary tumors.

Endoscopic Management

Recommendations

1. ERCP with balloon dilatation is recommended for PSC patients with dominant stricture and pruritus, and/or cholangitis, to relieve symptoms (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence) [64–68].

2. PSC with a dominant stricture seen on ima–ging should have an ERCP with cytology, biopsies, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), to exclude diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence) [69, 70].

3. PSC patients undergoing ERCP should have antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent post-ERCP cholangitis (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence) [71].

4. Routine stenting after dilation of a dominant stricture is not required, whereas short-term stenting may be required in patients with severe stricture (conditional recommendation, low qua–lity of evidence) [68, 72].

Definition

At cholangiography, dominant strictures are defined as stenoses measuring < 1.5 mm in the common bile duct or < 1.0 mm in the hepatic ducts [73]. Dominant strictures are common at the initial clinical presentation of PSC and frequently will develop over the course of the di–sease.

Benefits of Endoscopic Therapy

Endoscopic treatment of dominant strictures offers clinical benefit with diminished symptoms of pruritus or cholangitis, reduced cholestasis, and measureable improvement of strictures radiologically. The studies that reported these outcomes have been relatively small, uncontrolled, and retrospective, but their results have been generally favorable and reflect the experience of multiple academic centers managing almost 500 patients over several decades [64, 65].

Liver Transplantation

Recommendations

1. Liver transplantation, when possible, is recommended over medical therapy or surgical drainage in PSC patients with decompensated cirrhosis, to prolong survival (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [94–96].

2. Patients should be referred for liver transplantation when their Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score exceeds 14 (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [97].

PSC and IBD

Recommendations

1. Annual colon surveillance preferably with chromoendoscopy is recommended in PSC patients with colitis beginning at the time of PSC diagnosis (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [104].

2. A full colonoscopy with biopsies is recommended in patients with PSC regardless of the presence of symptoms to assess for associated colitis at time of PSC diagnosis (conditional recom–mendation, moderate quality of evidence) [3].

3. Some advocate repeating the exam every 3–5 years in those without prior evidence of colitis (weak recommendation, low quality of eviden–ce) [3].

Hepatobiliary Malignancies and Gallbladder Disease

Recommendations

1. Consider screening for cholangiocarcinoma with regular cross-sectional imaging with ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and serial CA 19-9 every 6–12 months (conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence) [107, 108].

2. Cholecystectomy should be performed for patients with PSC and gallbladder polyps > 8 mm, to prevent the development of gallbladder adenocarcinoma (conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence) [109].

Special Situations

Recommendations

1. Further testing for autoimmune hepatitis is recommended for patients with PSC < 25 years of age or those with higher than-expected levels of aminotransferases usually 5× upper limit of normal (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [1, 3].

2. MRCP is recommended for patients < 25 years of age with autoimmune hepatitis, who have elevated serum ALP usually greater than 2× the upper limit of normal (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [1].

General Management

Recommendations

1. Local skin treatment should be performed with emollients and/or antihistamines in patients with PSC and mild pruritus, to reduce symptoms (conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence) [123, 124].

2. Bile acid sequestrants such as cholestyramine should be taken (prescribed) in patients with PSC and moderate pruritus to reduce symptoms. Se–cond-line treatment such as rifampin and naltrexone can be considered if cholestyramine is ineffective or poorly tolerated (conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence) [124–126].

3. Recommend screening for varices in patients with signs of advanced disease with platelet counts < 150 •103/dl (conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence) [127].

4. Patients with PSC should undergo bone mineral density screening at diagnosis with dual energy X-ray absorption at diagnosis and repeated at 2- to 4-year intervals (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [128].

5. Patients with advanced liver disease should be screened and monitored for fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) [129].

Источник: Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015; published online 14 April 2015