Резюме

Актуальність. Дефіцит заліза (ДЗ) залишається значно поширеним станом серед дітей в Україні. ДЗ сприяє обтяженню перебігу патології шлунково-кишкового тракту в дітей і підлітків, проте вплив корекції латентного ДЗ на перебіг дисфункції жовчних шляхів на сьогодні не вивчений. Мета: визначити вплив корекції латентного ДЗ на клінічний перебіг дисфункції жовчного міхура і сфінктера Одді (ДЖМіСО) і стан обміну заліза в дітей шкільного віку. Матеріали та методи. Проведено дослідження «випадок — контроль», що включало 60 дітей 9–17 років, які проходили стаціонарне лікування з приводу загострення ДЖМіСО і мали латентний ДЗ. Діти були розділені на 2 групи: I — 30 пацієнтів, які отримували препарати заліза (50 мг елементарного заліза) щодня протягом 125 днів; II — 30 дітей, які не отримували препарат заліза. Проведено вивчення анамнезу, клінічне обстеження, загальний аналіз крові, розрахунок коефіцієнта насичення трансферину, визначено вміст сироваткового заліза, мікроелементів у волоссі, проведено спостереження протягом наступних 12 місяців. Результати. Дослідження показало, що застосування препарату заліза в дітей із ДЖМіСО і латентним ДЗ не тільки компенсує в них ДЗ, але й полегшує перебіг ДЖМіСО, знижуючи частоту загострень на 30,7 %. Висновки. Корекція латентного ДЗ із застосуванням препарату глюконату заліза, міді та марганцю полегшує клінічний перебіг ДЖМіСО і покращує стан обміну заліза в школярів.

Актуальность. Дефицит железа (ДЖ) остается широко распространенным состоянием среди детей в Украине. ДЖ способствует отягощению течения патологии желудочно-кишечного тракта у детей и подростков, однако влияние коррекции латентного ДЖ на течение дисфункции желчных путей в настоящее время не изучено. Цель: определить влияние коррекции латентного ДЖ на клиническое течение дисфункции желчного пузыря и сфинктера Одди (ДЖПиСО) и состояние обмена железа у детей школьного возраста. Материалы и методы. Проведено исследование «случай — контроль», включавшее 60 детей 9–17 лет, которые проходили стационарное лечение по поводу обострения ДЖПиСО и имели латентный ДЖ. Дети были разделены на 2 группы: I — 30 пациентов, получавших препараты железа (50 мг элементарного железа) ежедневно в течение 125 дней; II — 30 детей, не получавших препарат железа. Проведены изучение анамнеза, клиническое обследование, общий анализ крови, расчет коэффициента насыщения трансферрина, определено содержание сывороточного железа, микроэлементов в волосах, проведено последующее наблюдение в течение 12 месяцев. Результаты. Исследование показало, что использование препарата железа у детей с ДЖПиСО и латентным ДЖ не только компенсирует у них ДЖ, но и облегчает течение ДЖПиСО, снижая частоту обострений на 30,7 %. Выводы. Коррекция латентного ДЖ с применением препарата глюконата железа, меди и марганца облегчает клиническое течение ДЖПиСО и улучшает состояние обмена железа у школьников.

Background. Rates of iron deficiency (ID) remain high among children in Ukraine. ID contributes to burdened gastrointestinal pathology in children and adolescents, but evaluation of the impact of ID correction on the biliary tract dysfunction course is currently lacking. The objective was to determine the impact of latent ID correction on the clinical course of gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (GSOD) and iron status in schoolchildren. Materials and methods. A case-control study was conducted in 60 children aged 9–17 years, who had been undergoing the in-patient treatment for GSOD exacerbation and had latent ID. Children were divided into 2 groups: I — 30 patients treated with iron supplementation (50 mg elemental iron) daily for 125 days; II — 30 children having no iron supplementation. The study of anamnesis, clinical examination, complete blood count, determination of serum iron, transferrin saturation calculation, hair microelement profile evaluation, follow-up for 12 month were performed. Results. The study found that the use of iron supplement in children with GSOD and latent ID not only compensates ID in them, but also facilitates the GSOD course lowering the incidence of GSOD exacerbations by 30.7 %. Conclusions. Latent ID correction with combined iron, copper and manganese gluconate supplement facilitates the clinical course of GSOD and improves iron status in schoolchildren.

Статтю опубліковано на с. 9-13

Background

Children and adolescents are at high risk of iron deficiency due increased iron requirements secondary to intensive growth and puberty period [1]. Latent iron deficiency affects 47.12 % children in Ukraine [2] and is associated with poorer general health and wellbeing and higher levels of diseases [1, 3–5]. It is imperative that iron deficiency is effectively managed to prevent burdened course of coexisting gastrointestinal pathology as well as progression to anaemia. Increased dietary iron intake and iron supplementation are used to improve iron status [3, 9–11]. Systematic literature reviews have shown that dosing 1–2.5 mg/kg of elemental iron is used for correction of iron deficiency in children [1, 3, 4], however national guideline does not provide recommendation for doses of iron supplementation in children with latent iron deficiency (ID). Physiological metals copper, zinc, manganese are relational to iron metabolism in the human body and perform important functions connected with iron absorption in gut and functioning. Disturbed metabolism of these elements may lead to cell functio–ning impairment and, consequently, contribute to other diseases [8, 9].

Alternative materials are becoming increasingly popular in evaluation of provision by necessary trace elements. Concentration of trace elements in hair reflects the ave–rage content and body nutrition for longer time compared to other body materials [8]. It is a valuable source of information concerning body trace element balance for 2–3 month previously to taking the hair sample. Choice of hair as test material allows non-invasive material sampling causing no sense of discomfort in patients [8].

Previously, we have found burdened course of gallbladder and sphincter Oddi dysfunction (GSOD) in children with ID due to the high frequency of exacerbations, severe dyspeptic and asthenic-vegetative symptoms in the GSOD exacerbation [12].

The objective of this study was to determine the impact of latent ID correction on the clinical course of GSOD and iron status in schoolchildren.

Materials and Methods

A case-control study was conducted enrolling 60 children 9–17 years old who had been at in-patient treatment for exacerbation of biliary tract pathology in Children’s Hospital № 8, Kiev. The inclusion criteria were: 9–18 years old; clinical diagnosis GSOD; latent ID; history of GSOD at least 12 months from the first diagnosis; obtaining patients and his/her parents informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: age < 9 or > 18 years; concomitant disease of the gastrointestinal tract (gastritis, gastroduodenitis, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, enteritis, colitis); obesity, severe connective tissue dysplasia; dietary exclusion of meat or other animal protein containing food; refusal to participate in the study. Methods applied: study of anamnesis, clinical examination according to the current National Clinical protocol № 59 of 29.01.2013 [7], Complete Blood Count (CBC) at baseline and after 21 days from the enrollment, serum iron, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) indexes, percent transferrin saturation calculation, hair microelement profile evaluation by fluorescent spectrophotometry, follow-up for 12 month.

Latent ID was defined due to measure at baseline following blood and iron metabolism tests results: hemoglobin over 115 g/l for children under 12 years old; over 120 g/l for children 12–17 years old; over 130 g/l for boys over 14 years old, erythrocytes over 3,8 × 1012; low serum iron, increased TIBC, percent transferrin saturation (serum iron/TIBC × 100 %) below 17 %.

Hair trace element content evaluation was conducted at baseline and after 6 month from the enrollment. Ave–rage hair sample length and weight were 2.0 sm and 0.2 g, respectively. Spectrophotometry system used ElvaX-med, Elvatech, Ukraine.

The children were divided into 2 groups comparable by age, sex, duration of GSOD and iron metabolism tests results. Group I (30 patients) received treatment of GSOD according to the current National Clinical protocol № 59 of 29.01.2013 [7] (spasmolytics, cholagogue, therapeutic exercise) and a supplementation with medi–cinal product containing iron (as iron gluconate) 50 mg; manganese (as manganese gluconate) 1.33 mg; copper (as copper gluconate) 0.7 mg. for 125 days. Group II (30 patients) received treatment of GSOD according to the current National Clinical protocol № 59 [7]. In both groups children and their parents received detailed re–commendations for adjustment of children’s diet by iron containihg products.

Results

At the baseline, clinical examination revealed in all the patients abdominal pain and dyspeptic complaints and symptoms that are attributable GSOD exacerbation, as well as signs of asthenic-vegetative disorder and several or more symptoms related to iron deficiency (e.g. mild xerosis, xeroderma, split splitting hair, tongue papilla deformation, dental caries, angular stomatitis, geographic tongue, glossitis, pica chlorotica, involuntary urination when coughing or laughing, focuses of skin hyper- and depigmentation, koylonihia, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, nail transverse striations, exertional dyspnea, palpitation, muffled heart tones, etc.)

Results of baseline peripheral blood tests in patients are presented in tab. 1.

There were no significant differences in CBC, serum iron, total and latent iron binding capacity, transferrin saturation between the groups I and II at baseline.

Low content of iron (Fe) and iron metabolic related trace elements: copper (Cu), manganese (Mn) and zinc (Zn) was observed with high frequency at baseline in patients with GSOD and latent ID (fig. 1).

In 12–14 days after a successful in-patient treatment eliminating the clinical and laboratory signs of GSOD exacerbation all the children have been discharged home to continue treatment as the outpatients. At that point, abdominal pain as well as dyspeptic and asthenic-vegetative symptoms were absent in all patients of I and II groups. Follow-up was focused on detection of GSOD symptoms rebound as well as subsidence of clinical and laboratory signs of ID in patients.

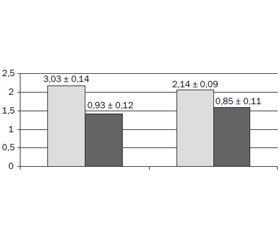

Follow-up analysis of blood findings at 21 day of treatment revealed a significant difference between I and II groups (tab. 2).

There was a statistically significant (p < 0.05) positive dynamics of hemoglobin, red blood cells, and the color index in group I. The peripheral blood test results in the group II did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) in 21 days from those had been taken at the start of the treatment. Although the end of the in-patient treatment elimination of clinical symptoms of GSOD had been achieved in all patients, at 3 months and 6 month follow-up after completion of therapy we observed recurrence of clinical symptoms of GSOD (tab. 3).

/9-13/11-1.jpg)

The positive treatment effect was observed for 6 months in patients of group I, demonstrating minor episodes of clinical manifestations GSOD when diet or day regimen violating. Absence or some minor clinical ID signs proved out the iron deficiency compensation in these patients. Children of group II in 39.3–75.0 % cases in the follow-up had clinical signs of GSOD (abdominal pain, dyspeptic and asthenic-vegetative symptoms). Clinical signs of ID found in 92.9 % of patients indicate the unimproved iron status after 6 month diet correction. 8 (28.6 %) patients in group II in 5–6 month catamnesis had recurrence of GSOD exacerbation.

Fig. 2 shows a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase of incidence of normal iron, copper and manganese content in the hair of children group l, confirming the normalization of iron copper and manganese meta–bolism in these patients. This indicates the effectiveness of the iron supplementation in group I. In the group II the frequency of reduced accumulation of iron copper and manganese in the hair of patients in 6 months follow-up remained unchanged (p > 0.05).

In group I where patients had received iron, copper and manganese supplementation a statistically significant reduction (p < 0.05) of the frequency of GSOD –exacerbations was achieved. Patients of group II showed unchanged GSOD exacerbation rates.

Discussion

Limited knowledge exists on the efficacy of diet correction and iron supplementation on iron status in children with gastrointestinal pathology and latent iron deficiency. Our study aimed to determine an impact of iron status correction on the GSOD course in children. GSOD and iron deficient patients who were recei–ving combined iron, copper and manganese gluconate supplementation had significant improvements in their peripheral blood and trace element status from baseline levels. Following this improvement, there was a statistically significant difference in test characteristics when compared to group receiving only diet corrected. This shows that iron supplement containing iron (as iron gluconate) 50 mg; manganese (as manganese gluconate) 1.33 mg; copper (as copper gluconate) 0.7 mg. for 125 days is effective in normalizing iron and trace element status in most patients, and that without such treatment iron stores in children with GSOD remain depleted. This study detected a difference in GSOD course in next 12 month follow-up between iron supplement and no iron supplement groups. The follow-up analysis revealed a significantly lower incidence of GSOD symptoms recurrence in iron supplement compared to no iron supplement groups. ID correction using iron, copper and manganese supplement in GSOD and latent ID children reduces GSOD exacerbation incidence on 30,7 %. This study is also informative concerning the data on treatment of latent iron deficiency in gastrointestinal disorder and GSOD patients that is limited.

/9-13/12-2.jpg)

Conclusions

1. A polidyselementosis was found in children with GSOD and latent ID indicated by reduced levels of iron, copper and manganese in hair of patients, showing a need to be corrected.

2. Adjustment of diet with high iron content products did no influence on GSOD children iron status presen–ting no improvement on blood test results and iron and other trace element content in the hair as well as high level of GSOD exacerbations in following 12 month.

3. Treatment with combined iron, copper and manganese gluconate supplement in children with GSOD and latent ID not only compensates their iron, copper and manganese deficiency and related ID symptoms, but also contributes to a mild GSOD course. This is confirmed by the low frequency of clinical GSOD symptoms for 6 months after treatment compared with no iron supplementation patients and decrease the of frequency of GSOD exacerbations on 30.7 % a year.

Conflicts of Interest. Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Список литературы

1. World Health Organization. Iron deficiency anaemia: Assessment, prevention, and control. A guide for programme managers. — Available online: http://www.who.int/nutrition/ publications/en/ida_assessment_prevention_control.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2016)

2. Shadrin O.G., Hayduchyk G.A. Problems of nutrition of infants and solutions // Ukrainian Medical Journal. — III/IV 2016. — 2(112). — 68-69.

3. Goddard A.F., James M.W., McIntyre A.S., Scott B.B., British Soc G. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia // Gut. — 2011. — 60. — 1309-1316. — doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228874 [PubMed].

4. Mozaffari-Khosravi H., Noori-Shadkam M., Fatehi F., Naghiaee Y. Once Weekly Low-dose Iron Supplementation Effectively Improved Iron Status in Adolescent Girls // Biol. Trace Elem. Res. — 2010. — 135. — 22-30. — doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8480-0 [PubMed].

5. Order of MOH Ukraine of 02.11.2015 № 709. Unified clinical protocols of primary, secondary (specialized) medical care in iron deficiency anemia (Regulations Ministry of Health of Ukraine).

6. Leonard A.J., Chalmers K.A., Collins C.E., Patterson A.J. Comparison of two doses of elemental iron in the treatment of latent iron deficiency: Efficacy, side effects and blinding capabilities // Nutrients. — 2014. — 6. — 1394-1405. — doi: 10.3390/nu6041394 [PubMed].

7. Order of MOH Ukraine of 29.01.2013 № 59. Unified clinical protocols of medical care for children with diseases of the digestive system (Regulations Ministry of Health of Ukraine).

8. Qayyum M., Shah M. Comparative assessment of selected me–tals in the scalp hair and nails of lung patients and controls // Biol. Trace Elem. Res. — 2014. — 158. — 305-322. — doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-9942-6 [PubMed].

9. Blanton C. Improvements in iron status and cognitive function in young women consuming beef or non-beef lunches // Nutrients. — 2013. — 6. — 90-110. — doi: 10.3390/nu6010090 [PubMed].

10. Peyrin-Biroulet L., Williet N., Cacoub P. Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency across indications: a syste–matic review // Am. J. Clin. Nutr. — 2015. — 102(6). — 1585-94. — doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.103366 [PubMed].

11. Tolkien Z., Stecher L., Mander A.P., Pereira D.I., Powell J.J. Ferrous sulfate supplementation causes significant gastrointestinal side-effects in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis // PLoS One. — 2015, Feb 20. — 10(2). — 73-83.

12. Marushko U.V., Nagorna K.I. Biliary dysfunction in children with iron deficiency // Zdorovie rebenka. — 2016. — 3(71). — 16-20.

/9-13/10-2.jpg)

/9-13/10-1.jpg)

/9-13/11-1.jpg)

/9-13/12-1.jpg)

/9-13/12-2.jpg)