Международный эндокринологический журнал Том 15, №7, 2019

Вернуться к номеру

Кореляція між цукровим діабетом 2-го типу та кісточково-плечовим індексом у географічно специфічній популяції Греції без захворювань периферичних артерій

Авторы: Koufopoulos G., Pafili K., Papanas N.

Diabetes Centre-Diabetic Foot Clinic, Second Department of Internal Medicine, Democritus University of Thrace, University Hospital of Alexandroupolis, Greece

Рубрики: Эндокринология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

Актуальність. Цукровий діабет (ЦД) залишається на сьогодні одним із найбільш швидко зростаючих за частотою та найскладніших захворювань. Кісточково-плечовий індекс (КПІ) — це співвідношення артеріального тиску нижніх кінцівок до артеріального тиску верхніх кінцівок. Визначення КПІ є одним із найдоступніших неінвазивних методів діагностики захворювань периферичних артерій. Вимірювання КПІ рекомендується Американською діабетичною асоціацією у всіх суб’єктів віком понад 50 років. Поширеність аномального КПІ доволі значна у хворих на ЦД 2-го типу. КПІ ≥ 1,3 асоціюється з підвищеним ризиком серцево-судинних захворювань та смертності серед загальної популяції, а також із загальною причиною смертності від ЦД. Мета дослідження: оцінити потенційний зв’язок кісточково-плечового індексу із цукровим діабетом у конкретної грецької популяції без захворювань периферичних артерій. Матеріали та методи. У період із липня 2017 р. по серпень 2018 р. обстежували осіб віком понад 30 років із ЦД 2-го типу. У дослідження включено 240 осіб (118 чоловіків) із середнім віком 64,5 ± 14,6 року з острова Наксос у Греції, у яких не було захворювань периферичних артерій. З них 144 мали ЦД, а 96 — ні. Тривалість ЦД становила 10,6 ± 7,4 року. КПІ вимірювали у всіх суб’єктів у положенні лежачи після 5–10 хвилин відпочинку при нормальній кімнатній температурі (25 °C) після того, як пацієнти зняли взуття та шкарпетки. Результати. Нами згруповано вимірювання КПІ в 4 групи: КПІ 0,90–1,29; КПІ 1,30–1,39; КПІ 1,40–1,49; КПІ > 1,50. КПІ > 1,30 спостерігали в 44 % учасників із ЦД порівняно з 3,1 % осіб без ЦД. Установлена вірогідна кореляція (р < 0,001) між тривалістю діабету та КПІ. Серед учасників, які страждають від ЦД, у пацієнтів із КПІ > 1,30 тривалість ЦД становила 14,2 ± 8,2 року, а з КПІ < 1,30 — 8 ± 5 років. КПІ виявився на 0,21 (19 %) вищим у суб’єктів із ЦД порівняно із суб’єктами без ЦД (1,28 ± 0,20 проти 1,07 ± 0,11, р < 0,001). Висновки. Високий показник кісточково-плечового індексу частіше спостерігається в грецьких учасників, в яких відсутні захворювання периферичних артерій, а також серед суб’єктів із тривалим перебігом цукрового діабету.

Актуальность. Сахарный диабет (СД) остается на сегодняшний день одним из наиболее быстро увеличивающихся по частоте и сложных заболеваний. Лодыжечно-плечевой индекс (ЛПИ) — это соотношение артериального давления нижних конечностей с артериальным давлением верхних конечностей. Определение ЛПИ является одним из самых доступных неинвазивных методов диагностики заболеваний периферических артерий. Измерение ЛПИ рекомендуется Американской диабетической ассоциацией у всех субъектов старше 50 лет. Распространенность аномального ЛПИ довольно значительна у больных СД 2-го типа. ЛПИ ≥ 1,3 ассоциируется с повышенным риском сердечно-сосудистых заболеваний и смертности среди общей популяции, а также с общей причиной смертности от диабета. Цель исследования: оценить потенциальную связь лодыжечно-плечевого индекса с сахарным диабетом в конкретной греческой популяции без заболеваний периферических артерий. Материалы и методы. В период с июля 2017 г. по август 2018 г. обследовали людей старше 30 лет с СД 2-го типа. В исследование включены 240 человек (118 мужчин) со средним возрастом 64,5 ± 14,6 года с острова Наксос в Греции, у которых не было заболеваний периферических артерий. Из них 144 имели СД, а 96 — нет. Длительность СД составила 10,6 ± 7,4 года. ЛПИ измеряли у всех субъектов в положении лежа после 5–10 минут отдыха при нормальной комнатной температуре (25 °C) после того, как пациенты сняли обувь и носки. Результаты. Нами сгруппированы измерения ЛПИ в 4 группы: ЛПИ 0,90–1,29; ЛПИ 1,30–1,39; ЛПИ 1,40–1,49; ЛПИ > 1,50. ЛПИ > 1,30 наблюдали у 44 % участников с СД по сравнению с 3,1 % лиц без СД. Установлена достоверная корреляция (р < 0,001) между продолжительностью диабета и ЛПИ. Среди участников, страдающих СД, у пациентов с КПИ > 1,30 длительность СД составила 14,2 ± 8,2 года, а с КПИ < 1,30 — 8 ± 5 лет. КПИ оказался на 0,21 (19 %) выше у субъектов с СД по сравнению с субъектами без СД (1,28 ± 0,20 против 1,07 ± 0,11, р < 0,001). Выводы. Высокий показатель лодыжечно-плечевого индекса чаще наблюдается у греческих участников, у которых отсутствуют заболевания периферических артерий, а также среди субъектов с длительным течением сахарного диабета.

Background. Diabetes mellitus (DM) remains one of the fastest growing and most challenging medical diseases today. The Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) is the ratio of ankle systolic blood pressure divided by brachial systolic pressure. Generally, ABI has a high specificity and sensitivity for the diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). In DM, ABI measurement is recommended by the American Diabetes Association for all subjects > 50 years old. The prevalence of an abnormal ABI is high in type 2 DM. An ABI ≥ 1.3 is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population, as well as with all-cause mortality in DM. The purpose of the study was to assess the potential association of a high ankle-brachial index with diabetes mellitus in a specific Greek population free from peripheral arterial disease. Materials and methods. Between July 2017 and August 2018, people over 30 years old with and without type 2 DM were examined. We included 240 subjects (118 men) with mean age 64.5 ± 14.6 years from Naxos island in Greece who did not have peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Of these, 144 had DM and 96 did not. DM duration was 10.6 ± 7.4 years. ABI was measured in all subjects. ABI was measured in the supine position after 5–10 minutes of rest, in normal room temperature (25 °C) after patients had taken off their shoes and socks. Results. We grouped ABI measurements into 4 groups: ABI 0.90–1.29; ABI 1.30–1.39; ABI 1.40–1.49; ABI > 1.50. ABI > 1.30 was seen in 44 % of participants with DM vs. 3.1 % of those without DM. There was a significant correlation (p < 0.001) between diabetes duration and ABI. Among participants with DM, those with ABI > 1.30 had DM duration of 14.2 ± 8.2 years, while those with ABI < 1.30 had DM duration of 8 ± 5 years. ABI was 0.21 (19 %) higher in DM vs. non-DM subjects (1.28 ± 0.20 vs. 1.07 ± 0.11, p < 0.001). Conclusions. A high ABI is more frequent in DM, PAD-free, Greek participants, especially among subjects with long-standing DM.

цукровий діабет; кісточково-плечовий індекс; діагностика; захворювання периферичних артерій

сахарный диабет; лодыжечно-плечевой индекс; диагностика; заболевания периферических артерий

diabetes mellitus; ankle-brachial index; diabetes mellitus; diagnosis; peripheral arterial disease

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) remains one of the fastest growing and most challenging medical diseases today [1]. The Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) is the ratio of ankle systolic blood pressure divided by brachial systolic pressure [2]. Generally, ABI has a high specificity and sensitivity for the diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) [3]. Its accurate measurement requires some training, but it can be carried out even by medical students [4, 5]. Thus, ΑΒΙ is very important as a diagnostic tool for PAD and an indicator of its severity [6–10].

In DM, ABI measurement is recommended by the American Diabetes Association for all subjects > 50 years old [11]. The prevalence of an abnormal ABI is high in type 2 DM [12]. An ABI ≥ 1.3 is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population [13–16], as well as with all-cause mortality in DM [17]. These high ABI values reflect poorly compressible vessels [18] characterised by medial arterial calcification [19–21]. Moreover, they have been associated with increased incidence of cardiovascular events in subjects with or without DM [16, 22, 23].

The purpose of this study was to assess the potential association of a high ABI with DM in a specific PAD-free population.

Materials and methods

Study subjects and setting

Between July 2017 and August 2018, people over 30 years old with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were examined. These were randomly recruited from General Hospital and from different regional medical centres of Naxos Island, Cyclades, Greece. The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of Human Rights and patients gave their informed consent.

In total, 240 subjects (118 men, 122 women; 480 limbs) were included. Of these, 144 had DM and 96 did not. Overall, mean age was 64.5 ± 14.6 years. DM duration was 10.6 ± 7.4 years.

Exclusion criteria included: type 1 diabetes mellitus; ABI < 0.9 or known PAD; intermittent claudication [24]; orthopaedic surgery of the lower extremities; vascular or endovascular intervention or surgery; coronary artery disease; diabetic foot ulcers.

Patients were grouped according to their location on the island, with subjects living in the flat part of Naxos –being marked as “low” and those in the mountainous part of the island (altitude > 380 meters) marked as “high”.

Ankle-brachial index

ABI was measured in the supine position after 5–10 minutes of rest, in normal room temperature (25 °C) after patients had taken off their shoes and socks [25]. A pneumatic cuff was placed around the ankle: ankle pressure was measured at the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries using a hand-held continuous-wave Doppler (8 MHz). The same technique was also used in both arms to measure brachial systolic pressure. The higher of the two ankle pressures was divided by the higher brac–hial systolic pressure. ABI was considered immeasurable when inflation of the blood pressure cuff to a pressure of > 250 mm Hg was insufficient to compress the arteries at ankle level [25–27].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS (Statistical package for Social Sciences, Chicago, IL) version 25.0. All data were reported as numbers (percentages), mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median, as appropriate. Chi-square test and Student’s two-tailed t-test were used for comparisons of nominal and numerical variants, respectively. Pearson’s correlation was used for ABI and diabetes duration. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

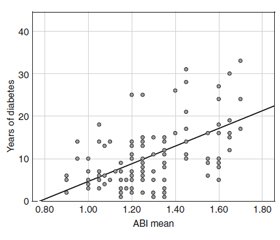

Demographics according to the presence or not of DM are summarised in table 1. We grouped ABI measurements into 4 groups: ABI 0.90–1.29; ABI 1.30–1.39; ABI 1.40–1.49; ABI > 1.50 (fig. 1). ABI > 1.30 was seen in 44 % of participants with DM vs. 3.1 % of those without DM. There was a significant correlation (p < 0.001; r = 0.67) between the linear increase of diabetes duration and ABI (fig. 2). Among participants with DM, those with ABI > 1.30 had DM duration of 14.2 ± 8.2 years, while those with ABI < 1.30 had DM duration of 8 ± 5 years. One third of DM subjects with ABI > 1.30 was 75–89 years of age.

On average, ABI was 0.21 (19 %) higher in participants with DM (1.28 ± 0.20) than those without DM (1.07 ± 0.11) (p < 0.001). Among DM participants, lowlanders had a 12.5 % higher ABI than highlanders (p < 0.001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to examine whether a high ABI is associated with DM or not and whether the latter is related to vascular risk factors in a PAD-free Greek population. The main findings of our study are: 1) DM subjects exhibited a 19% higher ABI than those without DM; 2) ABI > 1.3 suggestive of medial arterial calcification was more frequent in DM subjects; 3) a higher ABI was associated with longer DM duration.

Reaven P.D. et al. [28] have shown a strong correlation between DM and medial arterial calcification (assessed in coronary arteries and abdominal aorta) among 309 type 2 DM subjects with and without PAD. Indeed, high ABI values (> 1.3–1.4) are more frequent among DM subjects (presence or absence of PAD not mentioned) [29, 30] and have been repeatedly reported to correlate with longer DM duration [31, 32]. This was again shown in a study including 657 insulin dependent DM subjects with or without PAD [33]. In this study, medial arterial wall calcification (defined as ankle pressure 100 mm Hg higher than brachial pressure) was associated with DM duration, hypertension and dyslipidaemia [33].

Our study described an association between elevated ABI values and (especially long-standing) DM. Of note, PAD was defined as ABI < 0.9 or intermittent claudication. Nonetheless, pain perception may be blunted among subjects with diabetic peripheral neuropathy [34, 35]. Furthermore, a number of studies provide evidence that could limit the sensitivity of ABI for the diagnosis of PAD among DM subjects, especially when the latter is diagnosed though angiography [36] or non-invasive techniques other than ABI [14, 37, 38]. Indeed, a high prevalence of PAD (diagnosed by colour-flow duplex ultrasound scan) was reported among DM subjects with an ABI between 0.9 and 1.3 and > 1.3 [37]. Additio–nal evidence further suggested that elevated ABI (≥ 1.4) might mask leg ischaemia (toe-brachial index [TBI] ≤ 0.70 and/or low peak flow velocities ≤ 10 cm/s in the posterior tibial artery) in DM [14]. Indeed, in a study of both DM and non-DM subjects, elevated ABI (defined at various thresholds, i.e. 1.3, 1.4 and 1.5) in identifying PAD (defined as TBI < 0.60) exhibited 36–38 % sensiti–vity and 86–96 % specificity [38]. In the diagnosis of PAD (established by angiography) among DM subjects, the odds ratio of a false negative ABI was 4.36 (95% confidence interval 1.36–13.92, p = 0.013) [36].

These data point to the need of rigorous assessment of ABI among DM subjects, particularly among those with longstanding DM and those with multiple comorbidities [14, 28–39]. In this context, Espinola-Klein et al. [40] have proposed improving the diagnostic utility through the use of the lower systolic instead of the higher ABI divided by the higher of the left or right brachial systolic pressure. In a similar attempt, the use of different cut-off values of 1.0–1.1 was associated with the best diagnostic accuracy (highest sensitivity and specificity) for PAD among subjects with or without DM [41]. Finally, a study comparing ABI and TBI (evaluated by Doppler ultrasound or photoplethysmography) in 174 DM subjects and 53 controls has demonstrated that toe pressure measurement is more sensitive in determining perfusion pressure of the lower limbs in the case of ABI ≥ 1.3 [42].

The strengths of this study include the use of ABI and not only palpation of pulses, as well as the inclusion of a geographically specific population. Its limitations include the absence of serial ABI measurements, follow-up data and angiography, but these were beyond the scope of this work. Moreover, we did not assess participants for the presence of diabetic neuropathy and chronic kidney disease. Nonetheless, their association with ABI has previously been reported [30, 43, 44].

The practical implications of the present study may be outlined as follows. A higher ABI is associated with DM. Moreover, ABI > 1.3 suggestive of medial arterial calcification is more frequent in (especially long-standing) DM. Such values have been shown to mask decreased leg perfusion, especially among diabetic subjects [36–39]. Of additional note, among DM participants, lowlanders had a higher ABI than highlanders. This may be related to the healthier lifestyle rich in extra-virgin olive oil over the last decades [45], but requires further study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that high ABI is more frequent in DM, PAD-free, Greek participants, especially among subjects with long-standing DM. Our results add to the growing insight into the diagnostic uti–lity of ABI [46, 47].

Conflicts of interests. Authors declare the absence of any conflicts of interests and their own financial interest that might be construed to influence the results or interpretation of their manuscript.

/518-1.jpg)

/519-1.jpg)