Журнал «Здоровье ребенка» Том 16, №4, 2021

Оцінка психіатричних симптомів у дітей із целіакією та їх зв’язок із безглютеновою дієтою та материнськими факторами

Резюме

Актуальність. Мета дослідження: оцінити показники якості життя та прихильності до безглютенової дієти (БГД) у дітей із целіакією. Крім того, визначали значущість емоційного статусу матері з погляду психологічної корекції та відповідності призначення БГД пацієнтам із целіакією. Матеріали та методи. Дитячий опитувальник депресії (CDI), скринінг на тривожність і пов’язані з нею розлади в дітей (SCARED), опитувальник сили і труднощів (SDQ), опитувальник KINDer Lebensqualitätsfragebogen, шкала оцінки депресії Бека (BDI) і шкала оцінки тривожності Бека (BAI) були використані як у дітей із целіакією, так і у здорових дітей. Крім того, результати були зіставлені між пацієнтами з целіакією і здоровими учасниками дослідження. Результати. До дослідження ввійшли 47 пацієнтів із целіакією, 33 здорові дитини та їх матері. Рівень відповідності БГД, який був підтверджений тестами на антитіла, становив 41,7 %. Показники шкал CDI, SCARED та SDQ були значно вищими в пацієнтів із целіакією, ніж у здорових дітей. Крім того, загальні бали за KINDL були значно нижчими в групі учасників із целіакією. Більш високі показники шкали оцінки депресії Бека та шкали оцінки тривожності Бека були виявлені в матерів пацієнтів із целіакією, ніж у групі здорових дітей. У групі пацієнтів із целіакією була виявлена позитивна помірна статистично значуща кореляція між показниками шкали оцінки депресії Бека, шкали оцінки тривожності Бека і CDI, SCARED, SDQ. Також спостерігалася негативна статистично значуща кореляція між показниками шкали оцінки депресії Бека, шкали оцінки тривожності Бека в матерів і показниками за шкалою KINDL у дітей. Висновки. Підвищена поширеність психопатології та зниження якості життя були чітко продемонстровані в дітей із целіакією. Погіршення психосоціальної адаптації матері значною мірою пов’язане з депресивними симптомами в дітей із целіакією.

Background. The purpose was to evaluate the quality of life scores and the adherence of gluten-free diet (GFD) in children with celiac disease (CD). The other objective was to determine the relevance of the maternal emotional status between the psychological adjustments and GFD compliance of the patients with CD. Material and methods. Children’s depression inventory (CDI), Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders (SCARED), Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), KINDer Lebensqualitätsfragebogen Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) were administered to both children with CD healthy controls. Furthmore, the results were compared between the CD patients ant the healthy ones. Results. A total of 47 patients with CD, 33 healthy children and their mothers were enrolled. GFD-compliance rate, which was confirmed by antibody tests, was found to be 41.7 %. The scores of CDI, SCARED, and SDQ were significantly higher in CD patients than the healthy children. Moreover, the total scores of KINDL was significantly lower in CD group. Higher scores of BDI and BAI were found in the CD patients’ mothers than the healthy group. In patients group there were positive-moderate statistically significant correlation detected between score of BDI, BAI of mothers and CDI, SCARED, SDQ scores of children. There were also negative statistically significant correlation between scores of BDI, BAI of mothers and KINDL scores of children. Conclusions. Increased prevalence of psychopathology and reduced quality of life have been clearly demonstrated in children with CD. Worse maternal psychosocial adjustment significantly associated with depressive symptoms in pediatric CD patients.

Ключевые слова

целіакія; якість життя; безглютенова дієта; психопатологія; діти; підлітки

celiac disease; quality of life; gluten-free diet; psychopathology; children; adolescents

Introduction

Celiac Disease (CD) is a chronic T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation and villous atrophy in the small intestines. CD is common autoimmune-genetic disorder, accounting for the 0.5–1 % of general population1. Patients with CD suffer from lifelong intolerance to the gluten-containing grains and may present with various symptoms1. Only available treatment for now is gluten free diet (GFD) to which strict adherence is essential. Lack of dietary compliance cause a number of gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms2.

Psychological disorders and low quality of life may accompany the disease in patients with CD. Anxiety disorders, social phobia, panic disorder, depression and mood disorders are among the reported psychiatric disorders in these patients3. Although adherence to a GFD has been shown to be associated with reduction in depressive symptoms in children with CD4, difficulties in adhering to a GFD may also cause emotional, social, and behavioral problems in these children. Researchers conclude that psychological disturbances and poor quality of life are not only due to malabsorption related nutritional deficiencies but also because of challenges associated with strict dietary restrictions5.

Parental influence is important in the development of the child's coping skills and stress management6. Moreover children’s diet and preferences are influenced by their parents’ eating attitudes7. Thus, family support, parental attitudes related to GDF and also emotional status of parents are important environmental factors for adherence to a GFD in children with CD8.

In this study we purposed to evaluate the level of psychiatric symptoms and quality of life and their associations with adherence to GFD in CD diagnosed children. Additionally, effect of maternal emotional status on psychiatric status and GFD adherence of these children was examined.

Materials and Methods

Sample

A total of 47 children and adolescent (aged between 7–17 years) diagnosed with CD and their mothers were compared with 33 healthy children and their mothers. Parents and children were enrolled in this study after obtainment of verbal and written informed consent. Patients diagnosed with psychotic disorder, mental retardation, bipolar disorder and any other chronic diseases were excluded from the study. The mothers who were not able to read and write were also excluded.

Measures

Socio-demographic questionnaire. It includes socio-demographic data such as age, gender, GFD compliance (subjective), socio-economical level, educational state of parents, and medical history in family as well as information including schedule of dietary restrictions and laboratory results to obtain objective GFD compliance data.

Children’s depression inventory (CDI). CDI is a 27-item self-report measure designed by Kovacs. It has Turkish validity and reliability9. High scores indicate increasing depressive states. The cut-off point for the scale was accepted as 19.

Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders-SCARED. The SCARED is a brief self-report assessment designed to screen childhood anxiety disorders by Birmaher (1999)10. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of SCARED performed by Çakmakçı (2004)11. SCARED involves 2 forms for parents and children with 41 items each. Higher scores indicate higher anxiety state. SCARED form combined with sub-scales such as somatic/panic anxiety, generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, social anxiety and school phobia. The child form of this scale was used to determine the anxiety levels of the children who participated in our study.

Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). SDQ is a brief screening instrument developed to assess emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents by Robert Goodman (1997)12. Form consists of 25 statements that combined with 5 sub-scales; attention deficit and hyperactivity, emotional problems, behavioural problems, social problems, and peer problems. A separate score can be obtained for each subscale, and also the “Total Difficulty Score” can be measured with the sum of first four subscales. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of SDQ performed by Güvenir (2008)13. SDQ consists of 2 forms for parents and children. In this study, the parent self-reporting form, in which parents rate emotional and behavioral problems in their children, was used.

KINDer Lebensqualitätsfragebogen. Children Quality of Life Questionnaire. KINDL is a general purpose health-related quality of life measurement instrument particularly developed for children and adolescents by Ravens-Sieberer ve Bullinger (1998). KINDL includes different self-report forms for different age groups as well as a form for parental assessment. KINDL consists of 24 items and 6 dimensions including; physical well-being, emotional well-being, self-esteem, family, friends and school. Each dimension includes 4 items. KINDL items are rated from 1 (never) to 5 (always) using a 5-point likert type scale. The scores of the dimensions can be measured separately or the total quality of life score of these six dimensions can be obtained. Scores range between 0–100. Higher scores indicate good quality of life. In this study, parents were asked to fill in the Kindl-parent form to evaluate the quality of life of their child14.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The BDI is a self-report scale which contains 21 items. It developed by Beck (1978)15. Its Turkish validity and reliability version was performed by Hisli (2008)16. A total score is computed by summing the scores across items (range 1/4 0–63). The cut-off point for the scale was accepted as 17.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). The BAI is a self-report scale designed by Beck (1988) to measure anxiety symptom level17. Higher scores indicate higher anxiety state. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of BAI performed by Ulusoy (1993)18.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analysed with SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software for Windows (v21.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Individual and aggregate data were summarized using descriptive statistics including mean, standart deviations, medians (min-max), frequency distributions and percentages. Normality of data distribution was verified by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Comparison of the variables with normal distribution was made with Student t-test. The variables which were not normally distributed, the Mann Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests were conducted to compare between groups. Evaluation of categorical variables was performed by Chi-Square test. P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 47 children with CD, 33 healthy controls and their mothers included in the study. In patient group, mean age of the children was 12 years (ranged = 6–18), 59.6 % (n = 28) of them were girls and 40.4 % (n = 19) were boys. The patient and control groups were similar in terms of mean age, gender, mother's age, father's age, father's education, and family structure.

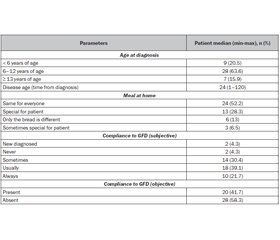

Thirteen of the parents (28.3 %) reported that they used to prepare specialized meal content to their children, while 24 (52.2 %) reported that the content of the meal was the same for all family members.

Patients and parents were questioned in the same interview about the patient's compliance with GFD. Ten (21.7 %) of the cases reported that they always followed the GFD, while 18 (39.1 %) of them reported that they generally followed the GFD. In addition, the GFD-compliance rate, which was confirmed by antibody tests, was found to be 41.7 % in case group. The characteristics of the patients in the CD group regarding diagnosis and dietary compliance are presented in table 1.

/31.jpg)

Although it was not significant, presence of a psychiatric diagnosis in the CD group (25.5 %) was more than the control group (9.1 %). The scores of CDI, SCARED, and SDQ were significantly higher in CD group than the control group. Moreover, the total scores and majority of subscale scores of KINDL was significantly lower in CD group than the control group. Similarly numerous subscales of SDQ and SCARED scales were found significantly higher in CD group. Furthermore, mean scores of BDI and BAI scales were higher in mothers of patients group (table 2).

/32.jpg)

There were no significant correlation found between the scores of CDI, SCARED, SDQ, KINDL and mean age, disease duration in CD group (p > 0.05). Similarly scores of BDI and BAI scales were not significantly correlated with mean age, disease duration, gender in mothers of patients group. Additionally, the age, gender, and duration of diagnosis had no significant effect on GFD compliance (objective) in the CD group. There were no differences according to the scores of CDI, SCARED, SDQ, KINDL as well as scores of BDI and BAI scales (in mothers) between the cases with and without GFD-compliance (table 3). There were positive-moderate statistically significant correlation detected between score of BDI, BAI in mothers and CDI, SCARED, SDQ scores in children. There were also negative-moderate significant correlation detected between score of BDI, BAI in mothers and KINDL scores in children (table 4).

Discussion

This study showed that the children with CD have more physiciatric symptoms than the healthy ones.

There are many barriers to compliance with the GFD such as; lack of awareness, social support, family sociocultural characteristics, self-management behaviors, education level, food contamination, inadequate food labeling, health-care system factors and psychological characteristics of patient. Non-adherence rate, which varies with methodology, sample size and sample characteristics, range from 5 to 70 % in published studies19. It has been documented that objective and subjective GFD-compliance outcomes are not always similar for the same sample group in CD patients. Machado et al. compared questionnaire scores with IgA-tTG test results in 46 CD-patients (mean age: 17 years). Serological test results revealed that 56.5 % of the CD-patients did not follow a GFD. On the other hand, 60.9 % of the patients reported full GFD compliance, but only 43.5 % presented negative serological test results and 35.7 % of those who reported strict compliance presented positive IgA-tTG20. Similarly in our study, ten (21.7 %) of the cases reported that they always followed the GFD, while 18 (39.1 %) of them reported that they generally followed the GFD. In addition, the GFD-compliance rate, which was confirmed by antibody tests, was found to be 41.7 % in case group. Fifty percent of the patients who proved objectively not to comply with the GFD reported that they generally followed their diet. Moreover, objective GFD compliance was found in only 5/18 of the cases who were reported to “generally follow the diet” by themselves and their parents.

CD has been associated with an increased prevalence of depressive symptoms and behavioral disorders in children and adolescents particularly before treatment period. Moreover, improvement in psychopathologies has been documented after GFD21. Sevinç et al. compared 52 CD-children with 40 healthy children. Researchers reported poor adherence rate (70 %) to GFD in CD group. Additionally, scores of emotional functioning, social functioning, school functioning, and total psychosocial health scales were significantly higher in CD group than the control group22. Similarly Kara et al. reported an increased levels of anxiety in children diagnosed with CD and also increased trauma symptoms in their mothers23. Giannakopoulos et al. documented significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression in CD patients and their parents than healthy controls24. In accordance with these data, the scores of CDI, SCARED, and SDQ were found significantly higher in CD group than the control group in present study. Similarly numerous subscales of SDQ and SCARED scales were found significantly higher in CD group. Mean scores of BDI and BAI scales were higher in mothers of patients group. Furthermore, there were positive-moderate statistically significant correlation detected between score of BDI, BAI in mothers and CDI, SCARED, SDQ scores in children.

Strict dietary restrictions and disease burden may negatively affect children diagnosed with CD. Therefore it is essential to measure quality of life while managing disease and screening the improvements. Stojanović et al. highlighted importance to include both children and parents in QOL measurements. Researchers also noted similar QOL scores and the differences in the scores of SCARED questionnaire between parents and their children25. Although significant associations have been documented between QOL and CD in children and adolescents, the findings are still debated26. Barrio et al. concluded that CD has no negative impacts on QOL in a study consisting of 1602 children and their parents27. On the contrary, Stojanović et al. reported that the mean score of QOL was significantly lower in children with CD (n = 116) than in the healthy controls (n = 116)28. Supportively in present study, the total scores and majority of subscale scores of KINDL was significantly lower in CD group than the control group. There were also negative-moderate statistically significant correlation detected between score of BDI, BAI in mothers and KINDL scores in children. But there were no statistically significant differences found according to the scores of KINDL between the cases with and without GFD-compliance.

Main limitation of this study was the small sample size of the patient group and was including the data from a single center but its' prospective study and the fact that a lot of testing has been done, the inclusion of mothers are the features that will contribute to the literature.

Conclusions

In conclusion, increased prevalence of psychopathologies and reduced quality of life have been clearly demonstrated in children diagnosed with CD. Particularly inappropriate family attitudes significantly associated with depressive symptoms. On the other hand, lack of GFD compliance has not been related to depressive symptoms or quality of life. Therefore, it is not only crucial to compliance with GFD for children but also essential to awareness of GF lifestyle for family in order to successful management of disease.

Received 09.04.2021

Revised 26.04.2021

Accepted 05.05.2021

Список литературы

1. Caio G., Volta U., Sapone A., Leffler D.A., De Giorgio R., Catassi C., Fasano A. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC medicine. 2019. 17(1). 1-20.

2. Di Nardo G., Villa M.P., Conti L., Ranucci G., Pacchiarotti C., Principessa L., Raucci U., Parisi P. Nutritional deficiencies in children with celiac disease resulting from a gluten-free diet: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2019 Jul. 11(7). 1588.

3. Coburn S.S., Puppa E.L., Blanchard S. Psychological comorbidities in childhood celiac disease: a systematic review. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2019, Aug 1. 69(2). 25-33.

4. Simsek S., Baysoy G., Gencoglan S., Uluca U. Effects of gluten-free diet on quality of life and depression in children with celiac disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2015, Sep 1. 61(3). 303-306.

5. Biagetti C., Gesuita R., Gatti S., Catassi C. Quality of life in children with celiac disease: A paediatric cross-sectional study. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2015, Nov 1. 47(11). 927-932.

6. Wagner G., Zeiler M., Berger G., Huber W.D., Favaro A., Santonastaso P., Karwautz A. Eating disorders in adolescents with celiac disease: influence of personality characteristics and coping. European Eating Disorders Review. 2015 Sep. 23(5). 361-370.

7. Knez R., Frančišković T., Munjas Samarin R., Nikšić M. Parental quality of life in the framework of paediatric chronic gastrointestinal disease. Collegium antropologicum. 2011, Sep 25. 35(2). 275-280.

8. Epifanio M.S., Genna V., Vitello M.G., Roccella M., La Grutta S. Parenting stress and impact of illness in parents of children with coeliac disease. Pediatric reports. 2013 Dec. 5(4).

9. Öy B. Children’s depression inventory: reliability and validity study. Turkish Psychiatry Journal. 1991. 2(2). 132-136.

10. Birmaher B., Brent D.A., Chiappetta L., Bridge J., Monga S., Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. Journal of the American academy of child & adolescent psychiatry. 1999, Oct 1. 38(10). 1230-1236.

11. Çakmakçı F.K. The reliability and validity study of the screen for child anxiety-related emotional disorders (SCARED). [Unpublished Expertise Thesis]. İzmit: Faculty of Medicine, Kocaeli University, 2004.

12. Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Сhild Рsychology and Рsychiatry. 1997 Jul. 38(5). 581-586.

13. Güvenir T., Özbek A., Baykara B., Arkar H., Şentürk B., İncekaş S. Güçler ve güçlükler anketi'nin (gga) Türkçe uyarlamasinin psikometrik özellikleri. Çocuk ve Ergen Ruh Sağlığı Dergisi. 2008. 15. 65-74.

14. Ravens-Sieberer U., Bullinger M. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res. 1998. 7(5). 399-407.

15. Beck A.T., Rush A.J., Shaw B.F. et al. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press, 1978. 229-256.

16. Hisli N. Beck Depresyon Envanteri’nin üniversite öğrencileri için geçerliği, güvenirliği. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi. 1989. 7. 3-13.

17. Beck A.T., Epstein N., Brown G. et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988. 56. 893-897.

18. Ulusoy М. Beck Anksiyete Envanteri: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Yayınlanmamış uzmanlık tezi. Bakırköy Ruh ve Sinir Hastalıkları Hastanesi, İstanbul. 1993.

19. Holbein C.E., Carmody J.K., Hommel K.A. Topical review: Adherence interventions for youth on gluten-free diets. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2018, May 1. 43(4). 392-401.

20. Machado J., Gandolfi L., Coutinho De Almeida F., Malta Almeida L., Puppin Zandonadi R., Pratesi R. Gluten-free dietary compliance in Brazilian celiac patients: questionnaire versus serological test. Nutr. clín. diet. hosp. 2013, Jan 1. 33. 46-49.

21. Coburn S., Rose M., Sady M., Parker M., Suslovic W., Weisbrod V., Kerzner B., Streisand R., Kahn I. Mental Health Disorders and Psychosocial Distress in Pediatric Celiac Disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2020, May 1. 70(5). 608-614.

22. Sevinç E., Çetin F.H., Coşkun B.D. Psychopathology, quality of life, and related factors in children with celiac disease. Jornal de pediatria. 2017, May 1. 93(3). 267-273.

23. Kara A., Demirci E., Ozmen S. Evaluation of psychopathology and quality of life in children with celiac disease and their parents. Gazi Med. J. 2019, Jan 1. 30. 43-47.

24. Giannakopoulos G., Margoni D., Chouliaras G., Panayiotou J., Zellos A., Papadopoulou A., Liakopoulou M., Chrousos G., Kanaka-Gantenbein C., Kolaitis G., Roma E. Child and Parent Mental Health Problems in Pediatric Celiac Disease: A Prospective Study. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2020, Sep 1. 71(3). 315-320.

25. Stojanović B., Kočović A., Radlović N., Leković Z., Prokić D., Đonović N., Jovanović S., Vuletić B. Assessment of quality of life, anxiety and depressive symptoms in Serbian children with celiac disease and their parents. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2019, May 1. 86(5). 427-432.

26. White L.E., Bannerman E., Gillett P.M. Coeliac disease and the gluten-free diet: a review of the burdens; factors associated with adherence and impact on health-related quality of life, with specific focus on adolescence. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016 Oct. 29(5). 593-606.

27. Barrio J., Román E., Cilleruelo M., Márquez M., Mearin M., Fernández C. Health-related quality of life in Spanish children with coeliac disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2016, Apr 1. 62(4). 603-608.

28. Stojanović B., Medović R., Đonović N., Leković Z., Prokić D., Radlović V., Jovanović S., Vuletić B. Assessment of quality of life and physical and mental health in children and adolescents with coeliac disease compared to their healthy peers. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo. 2019. 147(5–6). 301-306.

/31.jpg)

/32.jpg)

/33.jpg)