Журнал «Медицина неотложных состояний» Том 17, №5, 2021

Вернуться к номеру

Вибір знеболювання в пацієнтів, які надходять до відділення невідкладної допомоги з раковими болями: проспективне дослідження

Авторы: Şeref Emre Atiş(1), Bora Çekmen(2), Asım Kalkan(3), Öner Bozan(3), Mücahit Şentürk(3), Edip Burak Karaaslan(3)

(1) — Mersin Training Research City Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Mersin, Turkey

(2) — Karabuk University Medicine Faculty, Department of Emergency Medicine, Karabuk, Turkey

(3) — University of Health Sciences, Prof. Dr. Cemil Taşcıoğlu City Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

Рубрики: Медицина неотложных состояний

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

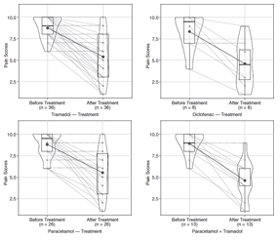

Актуальність. Гострий біль є однією з найпоширеніших причин, через які пацієнти з раком можуть потрапляти до відділення невідкладної допомоги. У нашому дослідженні ми порівняли ефективність знеболювальних препаратів, що застосовуються в онкохворих, які надійшли до відділення невідкладної допомоги зі скаргами на біль, а також переваги цих засобів одного над одним. Матеріали та методи. Біль у пацієнтів оцінювали під час надходження за допомогою візуальної аналогової шкали. Перед лікуванням реєстрували оцінку болю в балах. Хворих розподілили на чотири різні групи за типом проведеного лікування: нестероїдні протизапальні препарати; опіоїдні знеболювальні; парацетамол; парацетамол з опіоїдною терапією. Після лікування ми запитували, яке знеболювальне отримував пацієнт, і реєстрували оцінку болю. Результати. Було відзначено, що середній показник болю до і після лікування хворих у всіх групах знеболювальних препаратів статистично відрізнявся. Коли середні показники до і після лікування порівнювали за типами препаратів, не було виявлено різниці в зменшенні показників болю (p = 0,956 і p = 0,705, відповідно). Зроблено висновок, що середній показник болю до і після лікування пацієнтів, які вдома використовують нестероїдні протизапальні препарати й опіоїди, статистично не відрізнявся (p = 0,063). Висновки. При використанні нестероїдних протизапальних препаратів, парацетамолу або опіоїдів не встановлено переваги жодного засобу над іншими в онко-хворих із сильними гострими болями.

Background. Acute onset pain is one of the common reasons for cancer patients to present to the emergency department. In our study, we compared painkillers used in cancer patients admitted to the emergency department with pain complaints and their effectiveness and the superiorities of these painkillers in pain relief and their superiorities over each other. Materials and methods. The pain scores of the patients were asked at the time of admission by showing a visual analogue scale. Before treatment, pain scores were recorded. The patients were divided into four different groups according to the type of given treatment: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; opioid painkillers; paracetamol; paracetamol and opioid therapy. After the treatment, we asked which painkiller written in the treatment form was administered to the patient and recorded the pain score. Results. It was observed that the median pain score before and after treatment of the patients in all painkiller groups differed statically. When the median scores before and after treatment were compared according to drug types, no difference was found between the decrease in pain scores (p = 0.956 and p = 0.705, respectively). It was concluded that the pre-treatment and post-treatment median pain scores of patients who are using non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids at home did not differ statistically (p = 0.063). Conclusions. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol or opioids was not found to be superior to each other in patients with acute severe cancer pain.

нальгетики; біль при раку; невідкладна допомога; опіоїд; парацетамол

analgesics; cancer pain; emergency care; opioid; paracetamol

Introduction

Materials and methods

Results

/80.jpg)

Discussion

Conclusions

Limitations

- Patel P.M., Goodman L.F., Knepel S.A. et al. Evaluation of Emergency Department Management of Opioid-Tolerant Cancer Patients With Acute Pain. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2017. 54(4). 501-507. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.013.

- Tsai S.C., Liu L.N., Tang S.T., Chen J.C., Chen M.L. Cancer pain as the presenting problem in emergency departments: Incidence and related factors. Support Care Cancer. 2010. 18(1). 57-65. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0630-6.

- Vandyk A.D., Harrison M.B., MacArtney G., Ross-White A., Stacey D. Emergency department visits for symptoms experienced by oncology patients: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2012. 20(8). 1589-1599. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1459-y.

- Rivera D.R., Gallicchio L., Brown J., Liu B., Kyriacou D.N., Shelburne N. Trends in adult cancer-related emergency department utilization: An analysis of data from the nationwide emergency department sample. JAMA Oncol. 2017. 3(10). 172450. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2450.

- Burnod A., Maindet C., George B., Minello C., Allano G., Lemaire A. A clinical approach to the management of cancer-related pain in emergency situations. Support Care Cancer. 2019. 27(8). 3147-3157. doi:10.1007/s00520-019-04830-0.

- Reyes-Gibby C.C., Anderson K.O., Todd K.H. Risk for Opioid Misuse among Emergency Department Cancer Patients. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016. 23(2). 151-158. doi:10.1111/acem.12861.

- Caterino J.M., Adler D., Durham D.D. et al. Analysis of Diagnoses, Symptoms, Medications, and Admissions Among Patients With Cancer Presenting to Emergency Departments. JAMA Netw open. 2019;2(3):e190979. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0979.

- WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents. Accessed June 19, 2021. www.who.int.

- Fallon M., Giusti R., Aielli F. et al. Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2018. 29. iv166-iv191. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy152.

- Varrassi G., De Conno F., Orsi L. et al. Cancer pain management: An Italian delphi survey from the rational use of analgesics (RUA) group. J. Pain Res. 2020. 13. 979-986. doi:10.2147/JPR.S243222.

- Reyes C.C., Anderson K.O., Gonzalez C.E. et al. Depression and survival outcomes after emergency department cancer pain visits. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care. 2018. 9(4). e36-e36. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001533.

- Valeberg B.T., Rustøen T., Bjordal K., Hanestad B.R., Paul S., Miaskowski C. Self-reported prevalence, etiology, and characteristics of pain in oncology outpatients. Eur. J. Pain. 2008. 12(5). 582-590. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.09.004.

- Koob G.F., Stinus L., Moal M. Le, Bloom F.E. Opponent process theory of motivation: Neurobiological evidence from studies of opiate dependence. Neurosci Biobehav. Rev. 1989. 13(2–3). 135-140. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(89)80022-3.

/81.jpg)

/82.jpg)