Вступ

Поширеність куріння серед дорослого населення як в Україні, так і в усьому світі все ще залишається значною, незважаючи на досягнутий успіх у межах Рамкової конвенції ВООЗ з боротьби проти тютюну. Це передбачає майже неминучий вплив вторинного тютюнового диму (ВТД) на дітей і дорослих, які не курять [1–4]. Вторинний тютюновий дим (пасивне куріння; дим навколишнього середовища) є сумішшю диму від кінчика сигарети або іншого тютюнового виробу, що тліє (побічного), і диму, що видихається курцем (основного). Переважним компонентом ВТД є побічний дим, який, на відміну від основного диму, утворюється в умовах більш низької температури й містить у собі більші концентрації токсичних хімічних сполук, таких як нікотин, окис вуглецю та ін. Окрім ВТД існує також термін «третинний тютюновий дим», що використовується для позначення компонентів диму та їх метаболітів, які осаджуються на поверхнях [5]. Існує гіпотеза, що ці компоненти можуть всмоктуватись через шкіру, проковтуватися або вдихатися разом з пилом, однак потенційні наслідки для здоров’я третинного тютюнового диму продовжують вивчатися.

ВТД, який містить понад 250 шкідливих і понад 60 канцерогенних хімічних речовин, усе частіше розглядається як пряма причина розвитку неінфекційних захворювань серед осіб, які не є активними курцями [6].

За даними ВООЗ, майже половина всіх дітей у світі піддається впливу пасивного куріння, а 65 000 дітей щорічно помирають від хвороб, пов’язаних із ВТД. Найчастіше впливу ВТД діти зазнають вдома. Так, у США понад 40 % дітей віком до 1 року мешкають у будинках хоча б з одним курцем, а в Європі поширеність домашнього впливу ВТД на дітей раннього віку коливається від 10 до 60 % залежно від країни. Негативні наслідки впливу ВТД найбільш виражені в дітей перших п’яти років життя, особливо в сім’ях, де курцем є мати [7, 8]. Висока чутливість до пасивного куріння в дітей молодшого віку обумовлена фізіологічними особливостями їх організму (більші частота дихання й відносна площа легеневої поверхні, функціональна незрілість адренорецепторів гладких м’язів бронхів, нижча здатність до детоксикації канцерогенних хімічних речовин). Окрім того, діти залежні від дорослих, що передбачає постійний контакт із родичами, які курять; вони не здатні контролювати домашнє й соціальне середовище, а також свідомо уникати місць з високою концентрацією тютюнового диму, що також робить їх особливо сприйнятливими до впливу ВТД.

Можна виділити два шляхи негативного впливу тютюнового диму на здоров’я дитини: вплив на плід, якщо вагітна активно курить або експонована ВТД, і вплив ВТД на дитину після народження, якщо вона зростає під одним дахом з курцями. Однак пренатальну й постнатальну експозицію ВТД у дитини раннього віку складно відокремити, тому що в більшості випадків жінка або люди з її найближчого оточення не припиняють курити після народження дитини [9].

За результатами декількох метааналізів зарубіжних досліджень, активне куріння вагітної асоціюється з дворазовим збільшенням ризику мертвонародження (відносний ризик (ВР) 1,46 [95% довірчий інтервал (ДІ) 1,38–1,54]), значним ризиком передчасного розриву плодових оболонок і передчасних пологів (< 37 тижнів гестації) і помірним ризиком випадків викиднів (ВР 1,23 [95% ДІ 1,16–1,30]). Куріння жінки під час вагітності також було визначальним фактором низької ваги при народженні (< 2500 г) і народження дітей із затримкою внутрішньоутробного розвитку (ЗВУР) (ВР від 1,3 до 10,0) [10–12]. Вплив ВТД на вагітну жінку, яка не курить, хоча і меншого ступеня, також доведено асоціюється з патологічними станами перинатального періоду [13–15].

Говорячи про постнатальні наслідки впливу пасивного куріння на дитину, слід відмітити доведений зв’язок між ВТД і збільшенням частоти й тривалості патологічних симптомів з боку дихальної системи в дітей, таких як кашель, відходження мокроти й свистячі хрипи (візинг) (співвідношення шансів (СШ) від 1,23 до 1,5) [16]. Найвищий ризик патології дихальної системи спостерігався в дітей, у сім’ях яких курили обидва батьки. Вплив ВТД вірогідно підвищує ризик захворювань нижніх дихальних шляхів, а саме бронхіту й пневмонії (СШ 1,70 [95% ДІ 1,56–1,84]), а також посилює тяжкість перебігу респіраторно-синцитіальної вірусної інфекції в дітей першого року життя [17, 18]. Встановлено, що пасивне куріння пов’язане зі збільшенням поширеності й тяжкості бронхіальної астми й візингу в дітей [16, 17, 19]. Об’єднані дані систематичного огляду демонструють, що анте- і постнатальний вплив ВТД підвищує ризик розвитку бронхіальної астми на 20–85 %, особливо в дітей до двох років за умови куріння матері під час вагітності [20].

Пасивне куріння негативно впливає на частоту рецидивуючої інфекції середнього вуха, підвищуючи ризик виникнення на 30–46 % [21, 22]. ВТД вірогідно пов’язаний з розвитком хронічного риносинуситу й карієсу зубів у дітей [23, 24]. Доведено, що діти, які експоновані ВТД, частіше звертаються по допомогу в медичні заклади, а також довше знаходяться на госпітальному лікуванні [25].

Дані про значний вплив пасивного куріння роблять актуальним порівняння різних варіантів інтенсивності контакту дитини з ВТД (куріння матері до і після вагітності, куріння інших членів сім’ї, що перебувають під одним дахом з дитиною). Актуальним також є вивчення впливу ВТД від новітніх пристроїв доставки нікотину з огляду на зростаючу популярність останніх.

Мета дослідження: оцінити наслідки пренатального й постнатального впливу ВТД у дітей перших п’яти років життя.

Матеріали та методи

Для оцінювання несприятливих наслідків домашнього впливу ВТД на дітей перших п’яти років життя в рамках роботи школи здорової дитини, що функціонує на базі педіатричної клініки Одеського національного медичного університету, у ресурсі Google Forms був розроблений online self-reported опитувальник. Опитувальник («Анкета для батьків дітей перших п’яти років життя») складався з трьох доменів. Перший домен містив питання щодо даних раннього анамнезу й вигодовування дитини на першому році життя. У другій домен увійшли питання стосовно захворюваності дитини й особливостей перебігу в неї захворювань органів дихання, непереносимості дитиною певних харчових продуктів, а також даних сімейного алергологічного анамнезу. У третьому домені батьки надавали дані щодо соціального статусу родини, який визначався віком батьків, рівнями освіти й доходу, кількістю членів сім’ї в домогосподарстві й місцем мешкання родини. Рівень доходу самостійно визначався респондентами як низький, середній або високий. Питання третього домену також охоплювали історію вживання членами сім’ї тютюнових продуктів, включно із сучасними девайсами доставки нікотину.

В опитуванні взяли участь 520 респондентів. Критерієм включення в дослідження був вік дитини в сім’ї менше за 5 років; анкети з даними дітей, які народилися глибоко недоношеними (3–4-й ступінь) і мали спадкові захворювання бронхолегеневої системи, були виключені з аналізу. Усього протягом дослідження було проаналізовано 414 анкет, які відповідали критеріям включення й виключення. Під час аналізу даних усі діти були розподілені на дві групи залежно від експозиції ВТД. У першу (основну — ОГ) групу увійшло 186 дітей, які зазнали впливу ВТД на будь-якому етапі свого розвитку. У другу (контрольну — КГ) — 228 дітей без експозиції ВТД. Також основна група була розподілена на підгрупи залежно від періоду впливу ВТД, тобто пре- і постнатальний, а також залежно від того, хто курив поряд з дитиною — тільки мати, тільки батько або інші родичі або мати й родичі разом. Ми визначили пренатальний вплив ВТД на дитину як викурювання матір’ю принаймні однієї сигарети щодня протягом понад 6 місяців до початку вагітності й під час вагітності. Присутність постнатальної експозиції ВТД на дитину визначалась як викурювання матір’ю принаймні однієї сигарети щодня після народження дитини і/або куріння інших родичів у домогосподарстві.

Наявність наслідків пренатального впливу ВТД на дитину визначалась як народження дитини передчасно, а також присутність у дитини затримки внутрішньоутробного розвитку. Ми визначили дитину зі ЗВУР як дитину, яка народилася з масою тіла менше за 10-й процентиль за шкалою Фентона. Постнатальний вплив ВТД на дитину оцінювався за частотою гострих респіраторних вірусних інфекцій (ГРВІ) та госпіталізацій дитини з приводу цих захворювань на 1, 2 і 3-му роках життя, а також за частотою захворювань дихальної системи, ускладнених бронхообструктивним синдромом (БОС). БОС вважався присутнім, якщо в анкеті на питання «Чи спостерігали ви коли-небудь порушення дихання (задишку і/або свистячі (дистанційні) хрипи) під час ГРВІ у вашої дитини?» респондент давав позитивну відповідь і/або запис про цей стан був присутній у медичній документації дитини.

Аналіз даних здійснювався за допомогою програмного забезпечення Statistica 6.0 (серійний номер AXXR712 D833214FAN5). У цьому дослідженні дані були описані як поширеність (абсолютні й відносні показники) для якісних змінних, а також середні показники, стандартні відхилення (SD) або медіана для кількісних змінних. Т-критерій Стьюдента застосовувався для виявлення статистично значущої різниці в кількісних показниках (вага, довжина тіла, гестаційний вік дітей при народженні, вік переходу на штучне вигодовування, захворюваність і частота госпіталізацій) між групами. Проведено монофакторний аналіз з розрахунком співвідношення шансів і 95% довірчого інтервалу поширеності несприятливих наслідків у дітей, які зазнали й не зазнали пренатального й постнатального впливу сигаретного диму, а також для вивчення ролі ВТД як фактора розвитку пре- і постнатальних негативних наслідків для здоров’я дитини. Значущість фактора визначали при значенні СШ і його 95% ДІ понад 1.

Анкетування, обробку персональних даних, використаних при проведенні дослідження, здійснювали з урахуванням усіх етичних норм і стандартів, що стосуються проведення клінічних досліджень. Від усіх учасників була отримана письмова інформована згода на участь в опитуванні. Дослідження цілком відповідало етичним принципам Гельсінської декларації Всесвітньої медичної асоціації «Етичні принципи медичних досліджень за участю людини як об’єкта дослідження».

Результати

Співвідношення хлопчиків і дівчаток у досліджуваній когорті було 228 проти 186 (55,07 і 44,93 % відповідно). Середній вік дітей під час анкетування дорівнював 36,38 ± 7,19 (від 18 до 53) місяця, середній вік батьків — 30,80 ± 4,24 року. Середній розмір домогосподарства становив 4 особи й варіював від 2 до 6 мешканців. Респонденти переважно мали середній рівень достатку (77,54 [95% ДІ 73,27–81,29] %) і були мешканцями міста (98,39 [95% ДІ 95,37–99,45] %). 62,32 % дітей відвідували дитячі організовані колективи. Основна й контрольна групи дослідження були порівнянними за переліченими ознаками, окрім розподілу за рівнем освіти. У КГ статистично значуща більшість матерів мала вищий рівень освіти порівняно з ОГ (93,86 [95% ДІ 89,96–96,31] % проти 83,87 [95% ДІ 77,91–88,46] % відповідно).

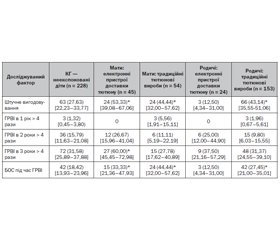

Загалом пренатального впливу ВТД зазнали 93 (22,46 %) дитини, у майже половини з яких (n = 45; 48,39 %) матері курили як до, так і під час вагітності. У дітей з пренатальною експозицією ВТД середній гестаційний вік становив 39,19 ± 1,34 тижня, середня маса тіла при народженні — 3424,84 ± 480,09 г, а середня довжина тіла — 53,29 ± 2,93 см. Показники фізичного розвитку й гестаційний вік новонароджених дітей, пренатально експонованих ВТД, не мали статистично значущих відмінностей порівняно з КГ. У підгрупі пренатального впливу тютюнового диму частка дітей, народжених передчасно, становила 3,23 % (95% ДІ 1,10–9,06 %; n = 3), а дітей із ЗВУР — 12,90 % (95% ДІ 7,54–21,21 %; n = 12), що також статистично вірогідно не відрізнялось від КГ. Однак аналіз даних залежно від періоду пренатального впливу ВТД, тобто тільки до або під час вагітності, показав, що куріння вагітної жінки значуще підвищувало ймовірність народження дитини зі ЗВУР (СШ 2,43 [95% ДІ 1,07–5,52]) порівняно з КГ. Було відзначено, що куріння матері під час вагітності призводить до зниження середньої маси тіла дитини при народженні майже на 350 г, однак статистична значущість цієї різниці не була підтверджена t-критерієм Стьюдента. Ми не зафіксували вірогідної різниці між КГ і групами жінок, які курили й не курили під час вагітності, щодо ризику передчасних пологів (табл. 1).

Постнатальний вплив ВТД було зафіксовано в 56,52 % дітей (n = 180). Порівняно з КГ діти з постнатальною експозицією ВТД майже вдвічі частіше перебували на штучному вигодовуванні (СШ 1,75 [95% ДІ 1,15–2,65]) з вірогідно меншим середнім віком переходу на адаптовані молочні суміші (p < 0,01). Більша частка дітей на штучному вигодовуванні зберігалась і при розподілі дітей на підгрупи залежно від того, хто саме курив у домогосподарстві. Частота використання адаптованих сумішей не відрізнялась від такої у КГ, якщо в домогосподарстві курили тільки родичі, але була значно вище, якщо тютюнові продукти використовували як мати, так і родичі (СШ 2,3 [95% ДІ 1,41–2,3]). У всіх сім’ях, у яких після народження дитини курила виключно мати, для годування використовувалися адаптовані молочні суміші.

У підгрупі постнатального впливу ВТД порівняно з КГ не було зафіксовано статистично значущої різниці в захворюваності дітей на ГРВІ на 1, 2 і 3-му роках життя. Однак у підгрупі дітей, у яких після народження дитини курила виключно мати, ризик розвитку ГРВІ понад 4 рази на рік на 3-му році життя підвищувався більше ніж у півтора рази (СШ 1,66 [95% ДІ 1,02–2,70]). Серед дітей з постнатальною експозицією ВТД частота захворювань дихальної системи, ускладнених БОС, становила 26,67 [95% ДІ 20,74–33,57] %, а в підгрупі куріння матерів досягала 39,39 [95% ДІ 30,34–49,24] %. Куріння будь-кого в домогосподарстві підвищувало ймовірність розвитку БОС під час ГРВІ у дитини в 1,61 (95% ДІ 1,01–2,58) раза, тоді як куріння виключно матері призводило до майже триразового збільшення ризику БОС (СШ 2,88 [1,70–4,86]) порівняно з КГ (табл. 2). Ми не зафіксували статистично значущої різниці в частоті госпіталізацій із приводу респіраторних захворювань серед дітей, постнатально експонованих ВТД.

/28.jpg)

За даними нашого дослідження, використання як традиційних тютюнових виробів, так і електронних систем доставки нікотину матерями після вагітності вірогідно значуще підвищувало частоту штучного вигодовування (СШ 2,10 [95% ДІ 1,14–3,86] і 2,99 [95% ДІ 1,56–5,76] відповідно). У підгрупі дітей, матері яких курили електронні прилади доставки нікотину, фіксувалося підвищення ризику частих ГРВІ (СШ 3,25 [95% ДІ 1,68–6,28]). Слід зазначити, що вживання традиційних тютюнових виробів і електронних систем доставки нікотину як матерями, так і іншими членами родини значно впливало на ризик розвитку БОС у дітей під час респіраторних захворювань (табл. 3).

Обговорення

У нашому дослідженні, як і в більшості наукових робіт, вживання тютюнових продуктів вагітними жінками було пов’язане з несприятливими наслідками вагітності, такими як ЗВУР і зменшення середньої маси тіла при народженні. Нами не було виявлено статистично вірогідної різниці в частоті передчасних пологів у групах і підгрупах дослідження [26–28]. Більшість наших результатів щодо постнатальних наслідків впливу ВТД на дитину збігаються з даними досліджень, що свідчать про підвищення ризику респіраторних захворювань, а також станів, які супроводжуються патологічними симптомами з боку дихальної системи у дітей, таких як задишка або свистячі хрипи (візинг) [29–31]. Слід зазначити, що в нашому дослідженні на частоту ГРВІ, а також респіраторних захворювань, ускладнених БОС, не впливало відвідування дитиною організованих дитячих колективів. За нашими даними, вживання тютюнових виробів також асоціюється з відмовою від грудного вигодовування дитини й раннім використанням адаптованих молочних сумішей [32, 33]. На нашу думку, постнатальні негативні наслідки експозиції ВТД можуть бути як обумовлені прямою дією компонентів тютюнового диму на дитину, так і опосередковано пов’язані з раннім штучним вигодовуванням. На відміну від інших досліджень нами не було доведено впливу ВТД на частоту госпіталізацій дитини.

Висновки

1. Куріння жінки під час вагітності в досліджуваній когорті є доведеним фактором ризику народження дитини зі ЗВУР (СШ 2,43 [95% ДІ 1,07–5,52]).

2. Куріння в домогосподарстві статистично вірогідно впливає на частоту й імовірність розвитку БОС у дітей перших п’яти років життя. Найбільший вплив на ризик розвитку БОС під час респіраторних захворювань у дитини має куріння матері (СШ 2,88 [95% ДІ 1,70–4,86]).

3. Використання сучасних електронних пристроїв доставки нікотину не знижує ризику розвитку захворювань, що супроводжуються БОС, у дитини. Як і у випадках куріння традиційних тютюнових виробів, найбільший вплив на здоров’я дитини перших п’яти років життя має використання таких приладів матір’ю (СШ 2,99 [95% ДІ 1,56–5,76]).

Конфлікт інтересів. Автор заявляє про відсутність конфлікту інтересів при підготовці даної статті.

Отримано/Received 07.02.2022

Рецензовано/Revised 18.02.2022

Прийнято до друку/Accepted 23.02.2022

Список литературы

1. Доповідь ВООЗ про глобальну тютюнову епідемію. 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204170/9789289055925-rus.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y.

2. Глобальне опитування дорослих щодо вживання тютюну: звіт. Україна, 2017. https://moz.gov.ua/uploads/1/8545-full_report_gats_ukraine_2017_ukr.pdf.

3. Eriksen M., Mackay J., Schluger N., Gomeshtapeh F., Drope J. The tobacco atlas. 5th ed. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; New York, NY: World Lung Foundation; 2015. www.tobaccoatlas.org.

4. Chuanwei M., Emerald G.H., Zilin L., Min Z., Yajun L., Bo X. Global trends in the prevalence of secondhand smoke exposure among adolescents aged 12–16 years from 1999 to 2018: an analysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys. The Lancet. 2021. 9(12). e1667-e1678. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2214-109X(21)00365-X.

5. Matt G., Quintana P., Destaillats H., Gundel L., Sleiman M., Singer B.C. et al. Thirdhand Tobacco Smoke: Emerging Evidence and Arguments for a Multidisciplinary Research Agenda. Enviromental Health Perspectives. 2011. 9(119). doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103500.

6. Raghuveer G., White D.A., Hayman L., Woo J., Villafane J., Celermajer D. et al. Cardiovascular Consequences of Childhood Secondhand Tobacco Smoke Exposure: Prevailing Evidence, Burden, and Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016. 134(16). e336-e359. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000443.

7. Hawkins S.S., Berkman L. Identifying infants at high-risk for second-hand smoke exposure. Child: care, health and development. 2014. 40(3). 441-445. doi: 10.1111/cch.12058.

8. Oberg M., Jaakkola M.S., Woodward A., Peruga A., Prüss-Ustün A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. 2011. 377(9760). 139-46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8.

9. Levine M.D., Cheng Y., Marcus M.D., Kalarchian M.A., Emery R.L. Preventing Postpartum Smoking Relapse: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016. 176(4). 443-52. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0248.

10. Pereira P.P., Da Mata F.A., Figueiredo A.C., de Andrade K.R., Pereira M.G. Maternal Active Smoking During Pregnancy and Low Birth Weight in the Americas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017. 19 (497). doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw228.

11. Kharkova O.A., Grjibovski A.M., Krettek A., Nieboer E., Odland J.Ø. Effect of Smoking Behavior before and during Pregnancy on Selected Birth Outcomes among Singleton Full-Term Pregnancy: A Murmansk County Birth Registry Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017. 14 (8). 867. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080867.

12. Blatt K., Moore E., Chen A., Van Hook J., DeFranco E.A. Association of reported trimester-specific smoking cessation with fetal growth restriction. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015. 125(6). 1452-1459. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000679.

13. Leonardi-Bee J., Britton J., Venn A. Secondhand smoke and adverse fetal outcomes in nonsmoking pregnant women: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011. 127(4). 734-41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3041.

14. Crane J.M., Keough M., Murphy P., Burrage L., Hutchens D. Effects of environmental tobacco smoke on perinatal outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2011. 118(7). 865-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02941.x.

15. Cox B., Martens E., Nemery B., Vangronsveld J., Nawrot T.S. Impact of a stepwise introduction of smoke-free legislation on the rate of preterm births: analysis of routinely collected birth data. BMJ. 2013. 346. f441. doi:10.1136/bmj.f441.

16. The Health Consequences of Smoking — 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), 2014. 7. Respiratory Diseases. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK294322.

17. Farber H.J., Groner J., Walley S., Nelson K. Protecting Children From Tobacco, Nicotine, and Tobacco Smoke. Pediatrics. 2015. 136(5). e1439-67. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3110.

18. Maedel C., Kainz K., Frischer T., Reinweber M., Zacharasiewicz A. Increased severity of respiratory syncytial virus airway infection due to passive smoke exposure. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2018. 53(9). 1299-1306. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24137.

19. Thacher J.D., Gruzieva O., Pershagen G., Neuman Å., Wickman M., Kull I., Melén E., Bergström A. Pre- and postnatal exposure to parental smoking and allergic disease through adolescence. Pediatrics. 2014. 134(3). 428-34. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0427.

20. Burke H., Leonardi-Bee J., Hashim A., Pine-Abata H., Chen Y., Cook D.G. et al. Prenatal and passive smoke exposure and incidence of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012. 129(4). 735-44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2196.

21. Carreras G., Lugo A., Gallus S., Cortini B., Fernandez E., López M.J. et al. Burden of disease attributable to second-hand smoke exposure: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine. 2019. 129. 105833. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31505203.

22. Tobacco Advisory Group. Passive smoking and children. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2010. https://shop.rcplondon.ac.uk/products/passive-smoking-and-children?variant=6634905477.

23. Christensen D.N., Franks Z.G., McCrary H.C., Saleh A.A., Chang E.H. A systematic review of the association between cigarette smoke exposure and chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery. 2018. 158(5). 801-16. doi: 10.1177/0194599818757697.

24. Tang S.D., Zhang Y.X., Chen L.M. et al. Influence of life-style factors, including second-hand smoke, on dental caries among 3-year-old children in Wuxi, China. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2020. 56. 231. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14566.

25. Merianos A.L., Jandarov R.A., Mahabee-Gittens M.E. Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Pediatric Healthcare Visits and Hospitalizations. AJPM. 2017. 53(4). 441-448. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.03.020.

26. Juárez S.P., Merlo J. Revisiting the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring birthweight: a quasi-experimental sibling analysis in Sweden. PLoS One. 2013. 8. e61734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061734.

27. Prabhu N., Smith N., Campbell D., Craig L.C., Seaton A., Helms P.J. et al. First trimester maternal tobacco smoking habits and fetal growth. Thorax. 2010. 65(3). 235-40. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.123232.

28. Benjamin-Garner R., Stotts A. Impact of smoking exposure change on infant birth weight among a cohort of women in a prenatal smoking cessation study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012. 15(3). 685-92. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts184.

29. Jones L.L., Hashim A., McKeever T., Cook D.G., Britton J., Leonardi-Bee J. Parental and household smoking and the increased risk of bronchitis, bronchiolitis and other lower respiratory infections in infancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir. Res. 2011. 12(1). 5. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-5.

30. Shi T., Balsells E., Wastnedge E., Singleton R., Rasmussen Z.A., Zar H.J. et al. Risk factors for respiratory syncytial virus associated with acute lower respiratory infection in children under five years: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health. 2015. 5(2). 020416. doi: 10.7189/jogh.05.020416.

31. Silvestri M., Franchi S., Pistorio A., Petecchia L., Rusconi F. Smoke exposure, wheezing, and asthma development: a systematic review and meta-analysis in unselected birth cohorts. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2015. 50(4). 353-62. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23037.

32. Cohen S.S., Alexander D.D., Krebs N.F., Young B.E., Cabana M.D., Erdmann P. et al. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018. 203. 190-196.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.008.

33. Suzuki D., Wariki W.M.V., Suto M., Yamaji N., Takemoto Y., Rahman M. et al. Secondhand Smoke Exposure During Pregnancy and Mothers’ Subsequent Breastfeeding Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep. 2019. 9(1). 8535. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44786-z.

/28.jpg)

/29.jpg)